On a freezing, overcast March day, the writer Jesmyn Ward made her first foray to Cleveland. She barely smiled as she stood behind a lectern in brown leather boots, red corduroy pants and a gray sweater set. Yet several in her audience at Cleveland Public Library murmured that the piercing, prepared remarks Ward read should be published immediately. Others were visibly moved and brimming with questions.

On a freezing, overcast March day, the writer Jesmyn Ward made her first foray to Cleveland. She barely smiled as she stood behind a lectern in brown leather boots, red corduroy pants and a gray sweater set. Yet several in her audience at Cleveland Public Library murmured that the piercing, prepared remarks Ward read should be published immediately. Others were visibly moved and brimming with questions.

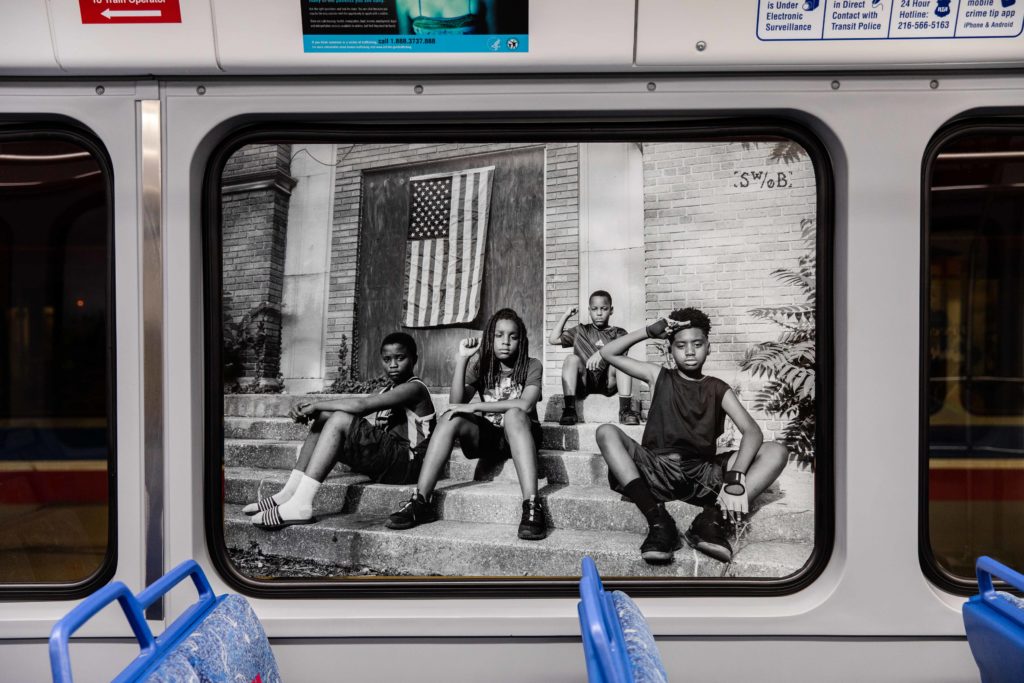

Ward, 36, who won a National Book Award for her second novel, “Salvage the Bones,” spent the morning with Cleveland students from Glenville High School and the afternoon exploring the question of who is allowed to speak: “We all feel inadequate when faced with a blank page, an empty canvas or a silent instrument. We must battle self-doubt or negative introspection with every sentence, every punctuation mark.”

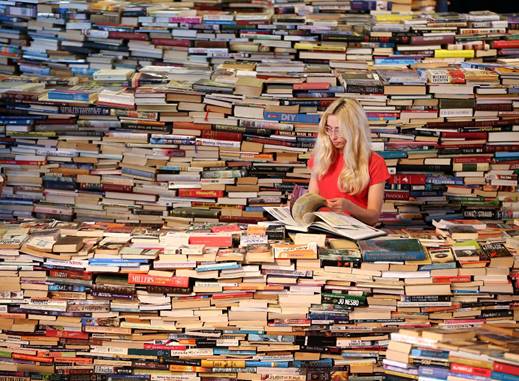

Growing up poor and black in rural Mississippi, Jesmyn wore hand-me-down clothes and ate meals stretched by food stamps. She envied classmates who could buy Scholastic books, even as she walked to the library, gravitating toward headstrong protagonists: Mary in “My Secret Garden” and Cassie in “Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry” and Claudia in “From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler.”

“Their environments were other worlds where I hid from the heat or my mother or my father or some other grown-up in my life,” Ward remembered. When her father lost his job at the local glass factory, her family moved in with Ward’s maternal grandmother. Fourteen people wedged into the house in coastal DeLisle, Mississippi—Jesmyn, her parents, two sisters and a brother; a cousin; her grandmother’s four sons and three daughters; plus the matriarch herself: “It was the first and only time I lived with so many people I loved.”

Ward’s fiction and her arresting 2013 memoir, “Men We Reaped,” beckons readers into this community. The title comes from Harriet Tubman: “We saw the lightning and that was the guns; and then we heard the thunder and that was the big guns; and then we heard the rain falling and that was the blood falling; and when we came to get in the crops, it was the dead men we reaped.”

The memoir centers on the October 2000 killing of Ward’s teenage brother Joshua by a drunk driver, and the violent, early deaths of four other young black men in their circle. Now a professor of creative writing at the University of South Alabama, Ward said she keeps returning to the site of her story — despite the poverty, racism and lingering damage from Hurricane Katrina, whose wrath Ward makes memorable in “Salvage the Bones.”

An active blogger and Twitter user, Ward identifies with communities on the margins. When a Cleveland reader – speaking for her book club — asked repeatedly if Ward was trying to foment social change, the author mildly eschewed the grandiose: “I hope that it changes the way readers think about people like me. If I can affect one reader, then by word-of-mouth, that makes a change over time.”

“The word ‘salvage’ is so close to ‘savage’,” Ward told her listeners. “It connotes resilience, fierceness and courage.” She describes her novel’s pregnant, teenage narrator, Esch Batiste, brushing off the ants and standing up after the hurricane, as the only thing she could do. “This is savage – you make a future from it, you tell your story, you survive.”

Ward said that when Hurricane Katrina cornered her own family, she swam to escape alongside her pregnant sister. The Wards sheltered in a tractor in an open field during a Level Five hurricane, she said, while a white farm family refused to take them in.

The Cleveland audience listened intently. One man called Ward’s voice “a smooth, velvet instrument.” One woman compared her writing to that of Edwidge Danticat, who won an Anisfield-Wolf Book award in 2005 for her novel “The Dew Breaker.” (Ward allowed that she had loved Danticat’s work since the novel “Krik? Krak.” ) A professor from Kent State University said she had added Ward to her syllabus.

Ward stressed the necessity of discipline and craft; she said her characters Skeeter and China (a pit bull) came out of a writing exercise during her MFA years at the University of Michigan. Still, Ward said, “my mother sometimes thinks I should return to school and study nursing. She is suspicious of writing.” Ward said her first stabs were stilted attempts to write about cellos and lives she didn’t know. “I was young and black and poor and a girl and I didn’t believe there was anything about my life worth exploring.”

She broke that barrier with a college entrance essay. It opened the door to Stanford. Like all of Ward’s work, it said “We are here. This is what life is like for us. Hear us.”

Laurie Kincer

March 27, 2014

Thank you for covering Jesmyn Ward’s visit to Cleveland with such eloquence and nuanced attention.