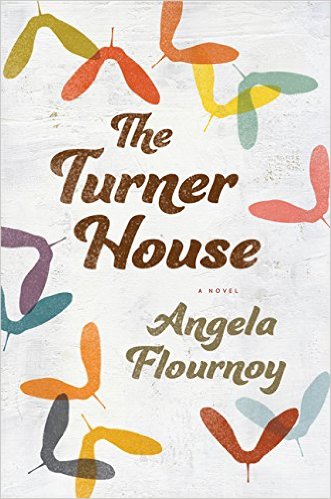

Spread over the opening pages of Angela Flournoy’s “The Turner House” is a family tree, its branches enumerating the 61 members of the Turner clan, the Detroit family at the heart of her engrossing debut novel. Inspired by her father’s Detroit upbringing and his 12 siblings, Flournoy makes her mark in modern literature with the Turners.

Spread over the opening pages of Angela Flournoy’s “The Turner House” is a family tree, its branches enumerating the 61 members of the Turner clan, the Detroit family at the heart of her engrossing debut novel. Inspired by her father’s Detroit upbringing and his 12 siblings, Flournoy makes her mark in modern literature with the Turners.

The Turner family home — a mint-green and brick single family structure on Detroit’s fictional Yarrow Street that served as its “sedentary mascot” — has seen 13 children come and go, and many more grandchildren and great-grandchildren walk through its doors. With matriarch Viola in failing health and patriarch Francis long deceased, the question of what to do with the house, its value plummeting, calls the Turner heirs together.

The home is more than just a childhood sanctuary; it’s the place where mysteries reside and secrets linger. Flournoy cuts to the quick, offering the defining mystery of the book in the first sentence: Are there haints (ghosts) in Detroit?

Turner family legend has it that eldest son Charles (nicknamed Cha-Cha) rumbled at midnight with a pale figure emitting a strange blue light. Even when five other Turner siblings corroborate the sighting, Francis Turner firmly insists, “There ain’t no haints in Detroit.” End of discussion. Fifty years later, the reappearance of the pale blue light prompts Cha-Cha to explore his childhood in depth.

Newly available in paperback, “The Turner House” made a splashy 2015 debut as a finalist for the National Book Award, the Center for Fiction First Novel Prize, the PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize for Debut Fiction and an NAACP Image Award. The skillful storytelling and realistic sense of history and place combine into an elegant and heartwarming narrative. The novel traffics in science-fiction, romance and historical fiction, but at its heart it’s a page-turner.

You don’t have to be a Detroiter to smell the Midwestern air, to see the crumbling neighborhoods, to feel the residential pride and worry as you flip the pages. After the youngest child, Lelah (now in her early 40s and newly evicted) seeks refuge in the empty Turner home, a neighbor comes over to check on the place, telling her of a recent squatter nearby: “Up in there like he paid rent, just living the life of Riley. Eatin her food and makin long-distance calls.”

Like most African-American families of the period, this story has its origins in the Great Migration, as Francis leaves Arkansas (and his new wife and son) to build a new life in the bright promise of Detroit and to send for his family after he gets settled. Stability proves hard to come by, however, and the reader is left wondering how Francis and Viola possibly reunite. Once they do (and eventually fill their hard-earned home with one child after another), it’s clear that the house means more to them than any mortgage deed could say.

The novel feels familiar to anyone with a sibling or two — the playful squabbles, the family meetings, the jockeying to be a parent’s favorite. There are very few missteps here, but a few siblings are barely present. Most of the story focuses on Cha-Cha and Lelah, the bookends of the Turner line. And a couple of outsider characters do prevent reader claustrophobia.

Flournoy told the National Book Foundation that she wanted to present both sides of life in Detroit — the well-documented struggles and the lesser-known cultural traditions that keep Detroiters smiling.

Numerous readers are likely to join in.