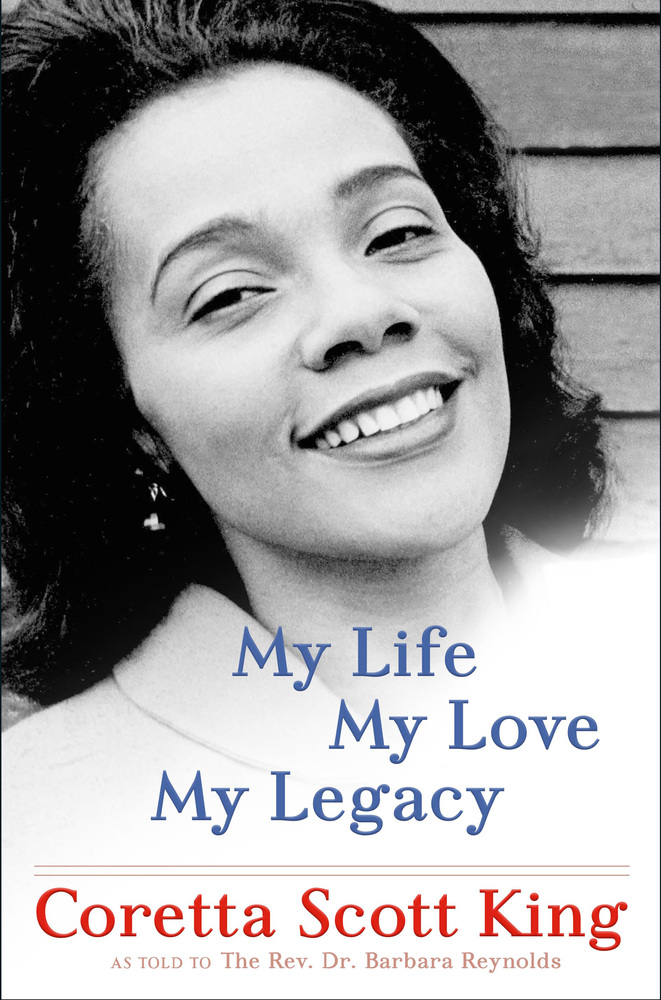

Coretta Scott King begins her posthumous new memoir with a terrific metaphor: “Most people know me as Mrs. King. The wife of, the widow of, the mother of, the leader of. . .Makes me sound like the attachments that come with my vacuum cleaner.”

When she died in 2006 at age 78, 12,000 people came to her eight-hour Georgia funeral, including four U.S. presidents. In this sweeping memoir “My Life, My Love, My Legacy” King details her rise from a restricted childhood in Marion, Alabama, to become one of the most visible leaders of the Civil Rights movement. But as King plainly states, most people were still unable to separate her legacy from her husband’s, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

She writes that this never bothered her: “We did not have a his-and-hers mission. We were one soul, one goal, one love, one dream. The movement had become embedded in my DNA. It was not something I could choose — or refuse.”

As a young girl in the segregated south, she encountered injustice early. When she was 15, racists burned her family’s Alabama home to the ground on Thanksgiving. Huddled around the melted vinyl, her father instructed them to pray for the arsonists. This incident was “my first taste of evil, the kind that shows up at your door in such a way that you can never forget its smell, its taste, its sting.”

She moved north soon after, enrolling at Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio, where she received her first taste of life outside of Jim Crow. Her studies then took her to the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, where she met Martin, a charismatic doctoral student who declared on their first date she would make a great wife.

They married in 1953 and had four children in succession — Yolanda, Martin III, Dexter and Bernice. King found it difficult to balance caring for young children and her music career while her husband was often orchestrating demonstrations, but she refused to be a stay-at-home mother. “I love being your wife and the mother of your children,” she shared with her husband one day, “but if that’s all I am to do, I’ll go crazy.”

Throughout the book, King bristles at being reduced to a background player. Her Freedom Concerts, well-attended international affairs in which she would use her classically trained voice to sing and tell stories about the movement, were one of the main fundraisers for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). She notes that she was the one who first began collecting her husband’s speeches and notes, the first to intuit their value. She was brave and outspoken in ways her husband couldn’t be, she wrote, noting that she began speaking out against the Vietnam War years before he felt comfortable doing so.

But her presence in the movement wasn’t always well-received. One incident, in which she accompanied the men to the gate of the Kennedy White House in a limousine, only to have to hail a cab back to the hotel, particularly stung. Men at the top, including her husband, were often reluctant to give female leaders public credit. In this memoir, she praises organizers Ella Baker, Fannie Lou Hamer, Juanita Abernathy and others for their ability to lead from the shadows.

For the most part, King’s memoir is beautifully written but cautious. She veers away from controversial topics such as her husband’s rumored extramarital affairs or the in-fighting between leaders. When she becomes introspective, on the verge of sorrow, she doesn’t linger there. Sadness and pity are luxuries she sets aside here, despite the horrors she endured.

King mentions just a few vacations with her husband during the height of the movement, always noting that they were “following doctor’s orders.” Toward the end of her life, she took a few trips with good friends Betty Shabazz, widow of Malcolm X, and Myrlie Evers-Williams, widow of Medgar Evers. The trio offered each other a particular sisterhood. When they were together, their main goal was to “enjoy not being in charge of anything,” King wrote.

King closes the book with a call to action: “Freedom is never really won. You earn it and win it with every generation.” This book may very well be the blueprint.