James Brown. John Brown’s raid. Michael Brown. Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka.

These subjects braid through Kevin Young’s new book, Brown, as he creates poems about black culture and boyhood, dividing his collection into “Home Recordings” and “Field Recordings.” It publishes this week.

“It’s a book that’s been brewing for a while,” Young told David Canfield of Entertainment Weekly. “The title poem is one I’ve been trying to write for some time, about growing up in Topeka, Kansas, and going to the church that Rev. Brown of Brown v. Board [pastored]. His daughter Linda played piano and organ in the church, and so to that connection to history always struck me as something worthy of a poem.”

Young dedicates this title poem to his mother and it closes out the section of home recordings. He begins it: The scrolling brown arms/of the church pews curve/like a bone – their backs/bend us upright . . .

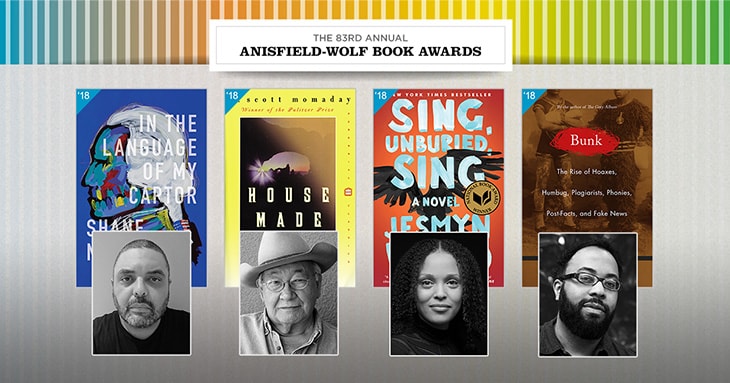

Young will be in Cleveland September 27 to accept the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award in nonfiction for his cultural history, Bunk: The Rise of Hoaxes, Humbug, Plagiarists, Phonies, Post-Facts and Fake News.

In Brown, 31 poems thread from boyhood and back, with a Triptych for Trayvon Martin subdivided into Not Guilty [A Frieze for Sandra Bland]; Limbo [A Fresco for Tamir Rice] and Nightstick [A Mural for Michael Brown].

The book is illustrated with beautiful endpapers of a child’s drawing of a collection of superheroes and nine black-and-white photographs by Melanie Dunea. In January 2015, she traveled to the Mississippi Delta with Young, as he writes, “to capture the spirit of that place with a poetry that enhances my own.”

Their pilgrimage took them to Greenwood, Miss, where the term “black power” was popularized at a Stokely Carmichael rally in 1966, and nearby Money, Miss., where Emmett Till was murdered. These poems call on the reader “to remember but also revisit and revise what we think of the past.” Young mentions in his notes that the white woman who accused Emmett confessed last year that he never whistled or called her baby. He didn’t do a thing.

“The site of Till’s lynching,” Young reports, “feels both holy and haunted.”

The 19 final lines of the book comprise a poem called “Hive.” It also concerns a boy:

The honey bees’ exile

is almost complete.

You can carry

them from hive

to hive, the child thought

& that is what

he tried, walking

with them thronging

between his pressed palms.

Let him be right.

Let the gods look away

as always. Let this boy

who carries the entire

actual, whirring

world in his calm

unwashed hands,

barely walking, bear

us all there

buzzing, unstung.