Eighteen months after the Unite the Right racist violence wracked Charlottesville, the 25th anniversary of the Virginia Festival of the Book gathered thousands of thoughtful citizens and served as one way to gauge the civic temperature.

That temperature was decidedly warm among poet Rita Dove and novelists Esi Edugyan and John Edgar Wideman, the trio who closed the festival with their session, “A World Built On Bondage: Racism and Human Diversity in Award-Winning Fiction.” It was the second consecutive year the festival culminated in an Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards panel.

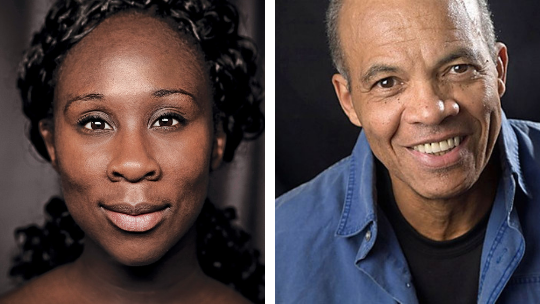

“Esi is a wonder,” Dove effused when introducing Edugyan, whose latest novel Washington Black weaves a tale of freedom and adventure told through the eyes of an 11-year-old boy of the same name. He begins his life in slavery on a Barbadian sugar plantation in the early 19th century. Edugyan received the Anisfield-Wolf award for fiction in 2012 for Half Blood Blues, a historical novel set to jazz in the folds of World War I and II.

The former United States Poet Laureate then turned to Wideman and told the audience, “I can’t remember a time — in my adult life — when I haven’t been accompanied by John’s work.” The 77-year-old nodded his head slightly as Dove rattled off his accomplishments, including a Rhodes scholarship, a MacArthur “genius” grant, all Ivy-League basketball player and an Anisfield-Wolf lifetime achievement prize in 2011.

The esteemed panel spoke of beginnings and how the path toward success often creates a chasm between where you’ve been and where you’re headed. For Wideman, that divide began as a basketball player on the high school varsity team, a pursuit that eventually led him to the University of Pennsylvania and away from his Pittsburgh roots.

“I felt quietly that I needed that,” Wideman said. “At home it was a world of women – my grandmother, mother, her friends. I loved it, but I wasn’t active in that world. I was listening. But I knew there was a different world for men . . . Where was that men’s world?”

He found that men’s world — rowdy, instructive — through sports. “Doing the things that made me successful in the world outside of my family was absolutely stepping away from that family,” Wideman said. “I could not sort that out, so I just pretended most of the time that it wasn’t happening. I blinded myself to it.”

That sort of isolation from one’s community presented itself as more of a cultural struggle for Edugyan, the daughter of Ghanaian immigrants who settled in Calgary, Alberta, the Canadian interior.

“I’m attracted to stories of people who are on the margins,” Edugyan, 41, said. “This comes out of my own history growing up a black woman in the prairies, in Alberta. Being born in Calgary, in the late 70s, where the black population has never been more than three percent.”

That dearth of community translated into her art: “I grew up with a huge feeling of isolation and almost of not having a community in that sense, and being sort of a constant outsider as I’m making my way through the world . . . That’s always been why I’m attracted to stories that are footnotes in the larger history . . . things that are sitting on the margins and looking at events through those eyes.”

Does writing feel like home? Dove asked. “Books opened the doors to feeling at home in the world,” Edugyan replied. “You learn that others, people who are totally unlike yourself, are going through the same thing, feeling the same emotions. There’s a great comfort in that.”

Wideman noted that his ease with writing ebbs and flows. But above all, he told the audience, language is art.

“Nobody owns the language,” he said. “Language is entirely invent-able by each one of you, each one of us, the language is a collective phenomenon. . . That’s what I hope to prove to people like myself: You own the world. It belongs to you. Language is an instrument. Language dances. It dreams. It contains silence.”

When it came to the power of the written word to offer a reprieve from the current news cycle and political climate, both authors had their reservations.

“Literature doesn’t solve problems,” Wideman told the audience. “Literature is the opportunity to think about problems, to invent in one’s own mind, and try to invent in other minds, a different world.”

“There’s no magic bullet novel that’s going to solve all our problems,” Edugyan quipped. “Empathy is important because we’re living in age right now where nobody is listening to anybody else. . . We need to engage with lives and experiences that are totally different from what we are going through ourselves. That’s the only way we can mark a path forward.”

When one white man in the audience asked Edugyan if buying a copy of Washington Black “would count as reparations,” the crowded auditorium sat silent for a few moments amid the pointedness of his insult.

Edugyan called it a terrible question, but she nonetheless answered it.

“One thing you might get – having walked with this young slave boy for six years, totally unlike yourself – is empathy,” she said. “You might feel something for him. Maybe it doesn’t change the greater world, this experience of empathy, but it offers something so rare, the experiences of someone totally different.”