Photo credit: Andy Snow

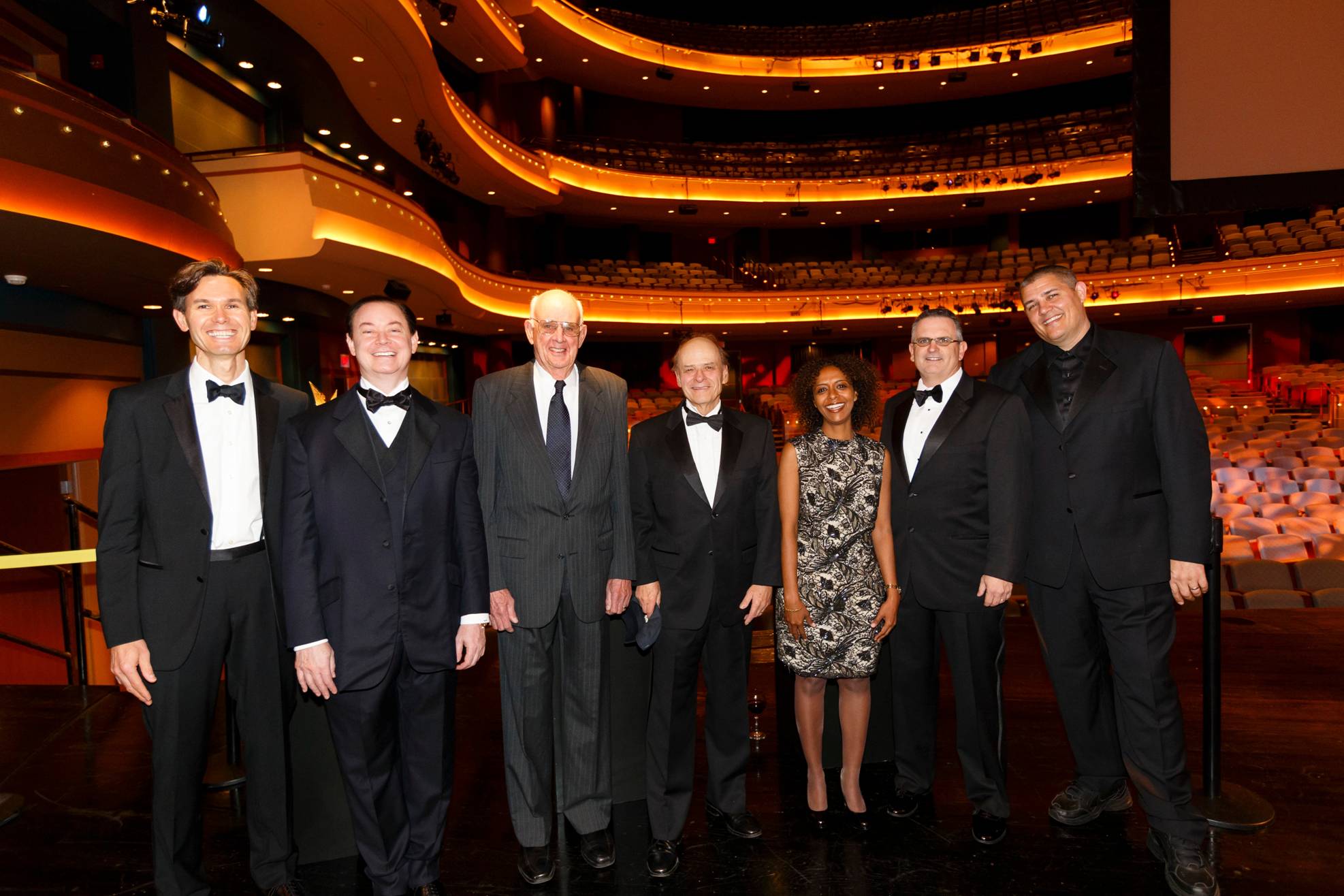

The potency of literature went on vivid display in early November when readers gathered around the writers who won this year’s Dayton Literary Peace Prizes. They started with an intense and intimate two-hour session at Sinclair Community College in downtown Dayton.

“I need to give a shout-out to Wendell Berry, whose ‘The Gift of Good Land’ was one of the most important books of my life,” boomed Sinclair President Steven Lee Johnson, turning to the celebrated Kentucky author in praise of the 1981 essay collection, one of Berry’s 50 titles.

A bit later, a woman in a pink sweater rose, lifted her chin to Berry and fiercely declared, “Your words have changed my life, over and over. I carry your books when I am sad and frightened and they have changed things for me.” She paused, looked at the 300-member audience. “How awesome is that?”

Berry, 79, in Dayton to accept his distinguished achievement award, decided to address the fervor. “When people say my writing has changed their life, I feel complimented, but also a little frightened,” he said. “I didn’t sit down to change anybody’s life.” His eyes sought out the woman. “I think my book spoke to something in you that changed your life. That is to your credit and you should not give the credit to me.”

Nevertheless, credit abounded at the Dayton Literary Peace Prize, a legacy of the 1995 Dayton Peace Accords that negotiated a stop to the Bosnian War. Established a decade later, the award seeks to recognize literature as “an enduring and effective tool for fostering peace.” It is now eight years old.

“The writers who win see the sincerity of the people who come and the people who work on this,” said Sharon Rab, founder and co-chair of the awards. “There is an entire community dedicated to peace and literature and the connection between the two.”

Pat Fife, a teacher at suburban Dayton’s Kettering-Fairmount High School, said her students were studying human trafficking with a class of like-minded students in Bosnia. Both groups read Ben Skinner’s “A Crime So Monstrous” about “modern-day slavery.” It won the 2009 Dayton prize.

“I thought it might be a little controversial, but people have been more than willing to engage it,” Fife said. Her students linked up with a nearby Methodist Church that works to fight human trafficking.

In its eight years, the Dayton Literary Peace Prize has overlapped often with the Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards. Both have honored Chang-Rae Lee, Junot Diaz, Edwidge Danticat, Ha Jin, Chimamanda Adichie and Isabel Wilkerson. And this year, each jury hit upon the same book in nonfiction: Andrew Solomon’s magisterial “Far From the Tree.”

In Dayton, Solomon declared that “human diversity matters just as much as species diversity.” He noted that roughly 50 years ago Time magazine could denigrate gays as sub-human and the Atlantic Monthly could recommend exterminating infants with Down Syndrome. “I wanted to understand how something universally understood as an illness turned into an identity,” he said.

Such transformation doesn’t arrive all at once. One man took Solomon aside in Dayton and demanded the writer admit that “this gay rights thing has gone too far.” Solomon quietly told the stranger he would not admit that.

The author, who received a thunderous ovation at the awards ceremony, riffed on his title. “What parent hasn’t looked at their child,” he asked, “and said, ‘What planet did you come from?’”

Growing up, Solomon read and admired Berry’s poetry, and Berry said, for his part, he was thunderstruck in 1963 by Harry Caudill’s nonfiction classic “Night Comes to the Cumberlands,” a story about rural poverty that mattered.

Maaza Mengiste, Dayton’s first runner-up in 2011 for her novel, “Beneath the Lion’s Gaze,” said she had been greatly influenced by Tim O’Brien, who was on hand as last year’s distinguished achievement winner.

“Peace is a shy thing,” O’Brien told the crowd. “It doesn’t brag about itself. We are at peace in this room and we take it for granted. It’s by its absence that peace is known. Peace is a value we don’t feel until the wolf is at the door.”

Fiction winner Adam Johnson spoke eloquently about the wolf’s stranglehold on North Korea, also captured in his Pulitzer-Prize winning novel, “The Orphan Master’s Son.” He asked the Dayton audience to imagine the isolation on the northern half of the peninsula, separated from its own literature. “Not a single play or poem has been smuggled out of North Korea in 60 years, unlike, even, the worse days of the Russian gulag.”

Closer to home, nonfiction runner-up Gilbert King explored “Devil in the Grove,” a harrowing, 1949 Florida case of racial injustice. It also won a Pulitzer Prize this year and centers on the legal mastery of a young Thurgood Marshall.

The crusading lawyer “was never surprised by the verdicts in the South,” King observed. “But he did say, ‘sometimes I get awfully tired of trying to save the white man’s soul.’”

International outrage over the “Grovewood boys” case in Florida helped raise the cash that supported the NAACP’s work on Brown vs. Board of Education, King said, ushering forward a new America.

Berry, lionized by O’Brien’s introduction, brought the crowd back to Earth. “There is a certain comedy in hearing one’s self praised,” he said. “I am embarrassed that I have nothing to present but me.”