LaTosha Brown, jazz singer and project director of Grantmakers for Southern Progress, told a story on herself: Having gleefully decided to break her diet, she passed a homeless man eating outside the Atlanta restaurant she had chosen. Brown went in, savored her fried chicken and saved half for later. When she exited, the man asked her for her leftovers.

On a stage in the Louis Stokes wing of the Cleveland Public Library, Brown stamped her foot, mimicking her frustration.

“I get this from my grandmother: if somebody tells me they are hungry, I don’t ask questions, I give them food,” she said. “But I had saved that chicken wing and I wanted it for dinner. I said, ‘You probably eat better than me.’ And he said, ‘You think I shouldn’t?’

“And I didn’t sleep all night.” Brown, a quarter century into her activism in civil rights, felt humbled. The man was right—she had considered herself more deserving, despite a lifetime as a church-going Christian.

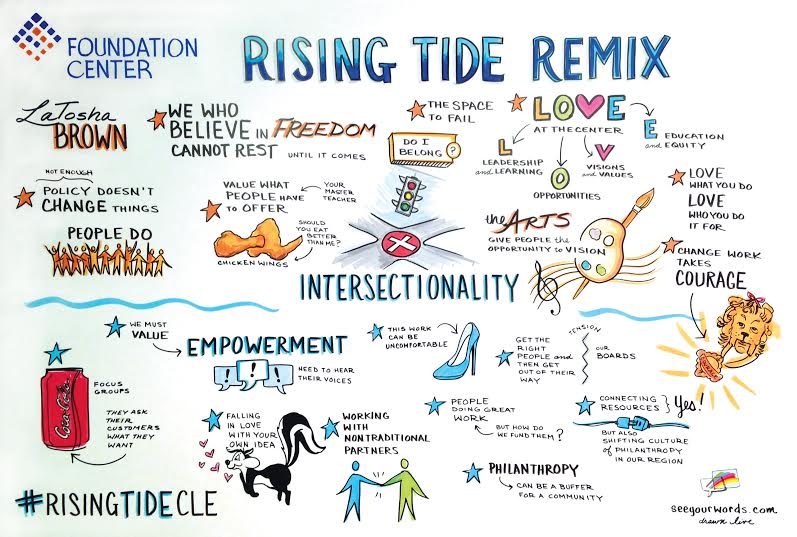

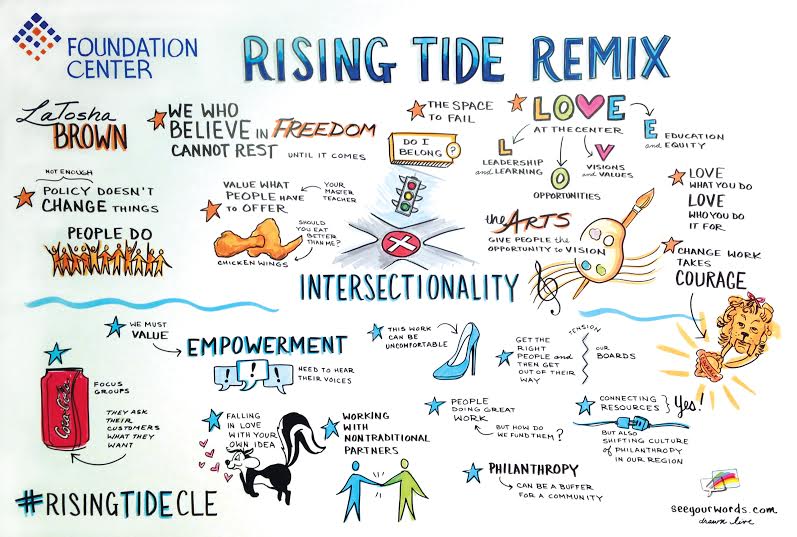

Brown challenged her listeners, gathered by the Foundation Center-Cleveland, to get uncomfortable, and to examine who makes them so. The audience, assembled to consider “the intersection of Black male achievement, LGBTQ issues and the empowerment of low-income women,” had real individuals to think about—thanks to a lightning round of storytellers, played back on tape.

Timothy Tramble spoke about his childhood in Cleveland’s Hough neighborhood as it is reflected today in the lives of young black men growing up in the Garden Valley Estates public housing, part of his territory as executive director of Burton, Bell, Carr Community Development, Inc.

“Many people growing up in a dysfunctional environment don’t recognize that dysfunction,” Tramble said. “To think out of the box, you need some time out of the box.” For him, that time was college.

Max Rivers, a new graduate of St. Martin de Porres High School, said he likes Chipotle, writing and sweaters – and wearing a tie. “I like the tie; makes me feel male, which is not always easy for me.”

Assigned female at birth, Max said he worked for his tuition and could not afford the surgery available to wealthier transgender people. He said he came out as male to his lesbian mother on Pride Day between his sophomore and junior years – a declaration she rejected. Now he worries his college applications will be voided as he legally changes his name.

For her part, Fatimah Zahra described herself as “a proud Cleveland State Viking,” having already earned an associate degree. The daughter of a single mom with eight children, Zahra said she grew up amid hunger and zero expectations.

“I literally came from nothing,” she said. “I didn’t feel like I was good enough. I had people tell me I wouldn’t be nothing, that I belonged in a kitchen. I was surrounded by drugs and violence and could have went down that route.”

Instead, she made her way to Seeds of Literacy, which tutored her toward a GED, earned on her third try. Zahra, the mother of a five-year-old son, told her story for “Rising Tide: Empowering Low-Income Women.”

Brown took in these stories and declared, “talk about intersectionality: too poor, too black, too gay. For all these folk, somebody always thinks they deserve more than them.”

Brown keynoted an afternoon called “Rising Tide: Remix,” seeded in a conviction that “a rising tide of philanthropic support and social innovation can solve entrenched problems and address community challenges head on.”

Brown said, “In philanthropy, we act upon people, we aren’t directed by them. And when people aren’t part of the change, they are not part of the change.”

Nelson Beckford, senior program officer for strong communities at the St. Luke’s Foundation, mused about whether any foundation would fund Mahatma Gandhi—with no board of directors, without other funders: “We probably wouldn’t fund him.”

Brown added, “Charity doesn’t necessarily create change . . .When we try to help the other without asking them how, we’re simply treating them as an experiment.”