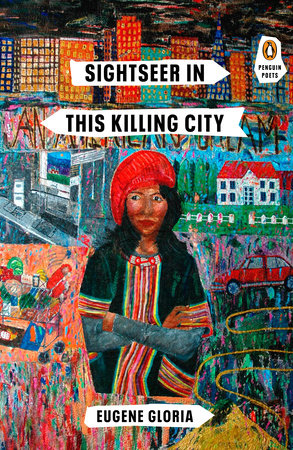

When a Missouri grand jury decided not to indict police officer Darren Wilson for killing 18-year-old Michael Brown, journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates watched his 15-year-old son Samori slowly stand up and walk into his own Baltimore bedroom to cry.

As Coates recounts this story in Between the World and Me, he writes that he followed his son, but did not hug or console him: “I did not tell you it would be okay, because I have never believed it would be okay. What I told you is what your grandparents tried to tell me: that this is your country, that this is your world, that this is your body, and you must find some way to live within all of it.”

Originally conceived as a collection of essays on the Civil War, Between the World and Me arrived four months ahead of its scheduled publication with a more urgent focus. Coates writes about the physical and psychological toll of being black in America, in the form of six letters/chapters to his son. Publisher Speigel and Grau bumped the release date up in response to the massacre of nine churchgoers in Charleston, as Between the World and Me “spoke to this moment.”

But the rush to get the book on shelves didn’t preclude Toni Morrison: “I’ve been wondering who might fill the intellectual void that plagued me after James Baldwin died,” Morrison had written. “Clearly it is Ta-Nehisi Coates.”

If Coates record-breaking 2014 reporting in “The Case for Reparations,” an Atlantic article, can be considered an intellectual appetizer, Between the World and Me serves as the entree.

Inspired by James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time, Coates has delivered a work that is as authoritative as it is inquisitive. Why can’t we, as a nation, come to terms with what we have wrought? Why do we constantly discuss “race” when we need to be eradicating racism? And perhaps most importantly, will we get it right anytime soon?

The Baltimore native connects his son’s disappointment in the Wilson non-indictment and the incident that hastened his own disillusionment with the American criminal justice system. In 2000, a Prince George’s County officer shot and killed Prince Jones, a Howard University student and friend of the author. This scorched Coates’ soul and psyche and he spends a sixth of his book writing about Jones.

He frames Jones’ slaying as an exemplar of what can befall the black body even in the best case scenario: a young man with a bright future, educated at some of the nation’s best schools, nurtured from birth toward greatness, bleeding to death outside his fiancee’s house in a case of mistaken identity. “Prince Jones was the superlative of all my fears,” Coates writes. “And if he, good Christian, scion of a striving class, patron saint of the twice as good could be forever bound, who then could not?”

Jones’ death is part of the reason Coates avoids shackling his son with “twice as good” generational mantra of black folks everywhere: “It struck me that perhaps the defining feature of being drafted into the black race was the inescapable robbery of time, because the moments we spent readying the mask or readying ourselves to accept half as much, could not be recovered….It is the raft of second chances for them and twenty-three-hour days for us.”

Not all in this book is grim. The most encouraging chapter centers on Coates’ undergraduate years at “The Mecca,” Howard University. Here he takes us on a virtual campus tour, leading up to the transformation many young adults undergo when they are learning on their own terms for the first time. He devours books three at a time and marvels that he’s walking in the footsteps of alumnae Lucille Clifton and Toni Morrison. Coates meets the woman he will marry, Kenyatta Matthews, a Chicagoan with a bit of wanderlust. (She inspired his first trip to Paris, where later this year, the couple and their son plan to relocate for a year.)

Read through my own lens as a black parent of black children, Between the World and Me is sobering. It offers no sense that the job will be made easier by magical conversations on how to navigate life safely in America. Coates’ parenting is blunt: “I have always believed that my job was not to hide the world from you but to guide you through it and this meant taking you into rooms where people would insult your intelligence, where thieves would try to enlist you in your own robbery and disguise their burning and looting as a celebration or a wake.”

One nitpick: In certain passages, Coates meanders around a subject as if figuratively speaking, he forgets his son is in the room. The message is still there, but the receiver is not so clear. Other reviewers have called into question whether Between the World and Me is too male-centric. Buzzfeed editor Shani O. Hilton writes that she was disappointed that the “black male experience is still used as a stand in for the black experience.”

Nevertheless, this book is a masterpiece, and here is a postscript: I would still like to read that Civil War book. What does one of the most fertile and curious minds of our era have to say about our nation’s deadliest war? He gives us a tease here, but let’s hope a full-bodied work is still on the way.

Between the World and Me goes on sale Tuesday, July 14.

Taya Dunn Johnson

July 14, 2015

Great review! I’ve been following/reading Coates for quite some time and I am looking forward to purchasing and reading this book.

Siobhan

July 14, 2015

Excellent review Tara! I just listened to Ta-Nehisi interview on podcast and after reading your review I’m intrigued to read his book. Thank you!

Shelly Rankins

July 14, 2015

Great review, Tara! Very good insight into the text and I appreciated your thoughts as a parent. Like most people, I’ve been following Mr. Coates career and I just listened to his NPR interview with Michele Norris. Can’t wait to get this book. Thank you.