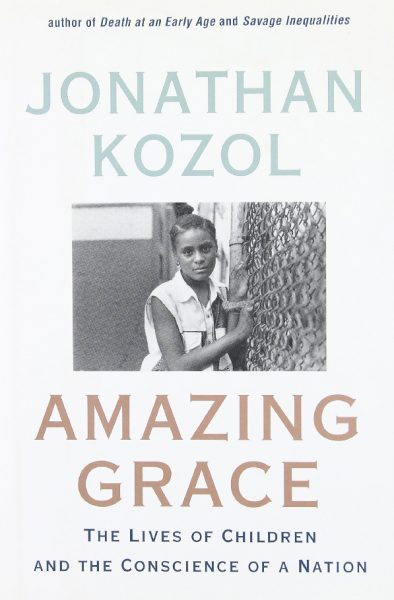

“god bless mommy. god bless nanny … god, don’t punish me because I’m black …” This is an excerpt of a prayer taken from one of the saddest, most disheartening books I’ve ever read. Jonathon Kozol based this book on a neighborhood in the South Bronx, called Mott Haven. Mott Haven happens to be not only the poorest district in New York, but possibly in the whole United States. Of the 48,000 living in this broken down, rat-infested neighborhood, two thirds are Hispanic, one third is black and thirty-five percent are children. Not only is Mott Haven one of the poorest places, it is also one of the most racially segregated.

The book itself is an on-going dialogue between Kozol and the neighborhoods residents, interjected every so often with thoughts from Kozol. He covers a spectrum of topics from AIDS, drug addiction, prostitution, crime, poorly run and funded schools, white flight from schools to over-crowded hospitals and the amazing faith in religion and God that many of these people have.

Kozol makes several trips to Mott Haven and speaks with a myriad of people, children and adults alike. For instance, Kozol develops a rapport with a twelve-year-old Hispanic boy named Anthony. Anthony is clever and loves to write stories. Some day he hopes to become a novelist. He also has a great faith in God. He makes some very poignant remarks pertaining to his neighborhood and life in general. For example, one day Kozol and Anthony are discussing if anyone in the neighborhood is truly happy and Kozol pints out that some of the children seem cheerful playing in the school playgrounds. Anthony quickly points out that cheerful and happy are not the same. Then as they are walking, Anthony stops and waves his hand around him in the neighborhood. Then he asks, “Would you be happy if you had to live here?” The only answer can be, NO.

Kozol also speaks to many of the church leaders in the different communities of the South Bronx. In particular, he speaks often to Reverend Overall, known as Mother Martha to Anthony and the other children that attend her church. What is most amazing about Rev. Overall is the fact that she gave up a productive career as a lawyer to serve the people in the poorest community in America. She provides solace to those who seek it, feeds many of the children in the neighborhood, and will take anyone to the hospital that needs to go.

Mrs. Washington knows far too well about the hospitals for the poor. Kozol speaks to this middle-aged woman more than anyone. Mrs. Washington contracted AIDS from a husband that she thought was faithful. She is quite sick and has to go to the hospital often, but according to the State of New York she is not yet sick enough to collect Social Security Insurance. She explains that sometimes you must sit in the waiting room of the hospital for three days or so before you are even seen or given a bed. When a room is available the nurses are usually so busy that Mrs. Washington ends up changing her own bedding. Often times the bed’s previous occupant has left the sheets soiled or blood-soaked.

Fortunately, Mrs. Washington has a son and a daughter that stand beside her and provides her with strength. Her daughter, Charlayne is in her last year at a two-year college and is holding down a part-time office job. She also has a five-year-old son and a six-year-old adopted daughter. The little girl is the biological child of a crack-addicted woman that Charlayne was once friends with. The prayer in the beginning is a prayer that these two young children say every night.

Mrs. Washington’s son, David has taken care of his mother and makes sure she eats and tries to keep her healthy. He also has been accepted to City University with total financial aid. He hopes to be a prison officer.

So, when I hear about the breakdown of the family and how the poor are lazy, I think of this family and wonder how the white middle class can make such judgments without really looking into the situation. Throughout the book some very good points are made about the “breakdown” of the family in these neighborhoods. When everything breaks down in a neighborhood, how is a family or children supposed to proper? When the pipes and electricity don’t work, and asthma runs rampant because of an incinerator strategically placed in the poorest and weakest of places, how does the spirit survive?

What is one of the saddest aspects of this book is that these children constantly are surrounded by death, sickness and drugs. Many of them live with grandmothers or other family members because their own parents are dead, in prison or too drug-addicted to care for them. When drug dealers are the only ones with some money in the neighborhood, who else do these children have to look up to, even if they know it is wrong?

For many race is a constant reminder of why they are so stigmatized. The simple fact that white students flee public schools when black students start to attend throws up a red flag to the black students that they are not thought of as “good enough”.

Many feel that they are in jail or “hidden”. As if America doesn’t have room for them. One young girl even explained that she thought if the people in New York were to wake up and find that they were all gone, that they would be relieved. She thinks that the people of New York and America look at them as obstacles to moving forward.

There are so many aspects to this book, but Kozol provides no solutions. He only gives us the side of the poor that many of us never see. The media and the politicians are usually too busy describing “bad” welfare mothers and criminal crack heads. They don’t take into consideration that these people are living on top of each other in sub-standard housing. I think Kozol’s purpose with this book was to represent the poor and to awaken America, especially white America, to the atrocities in our society.

Contributed by Johnna Jackson