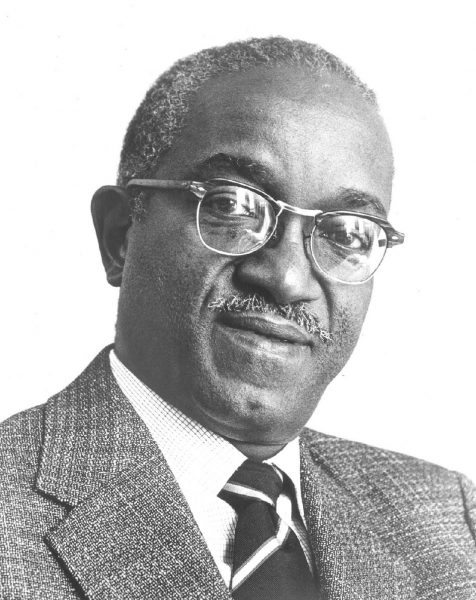

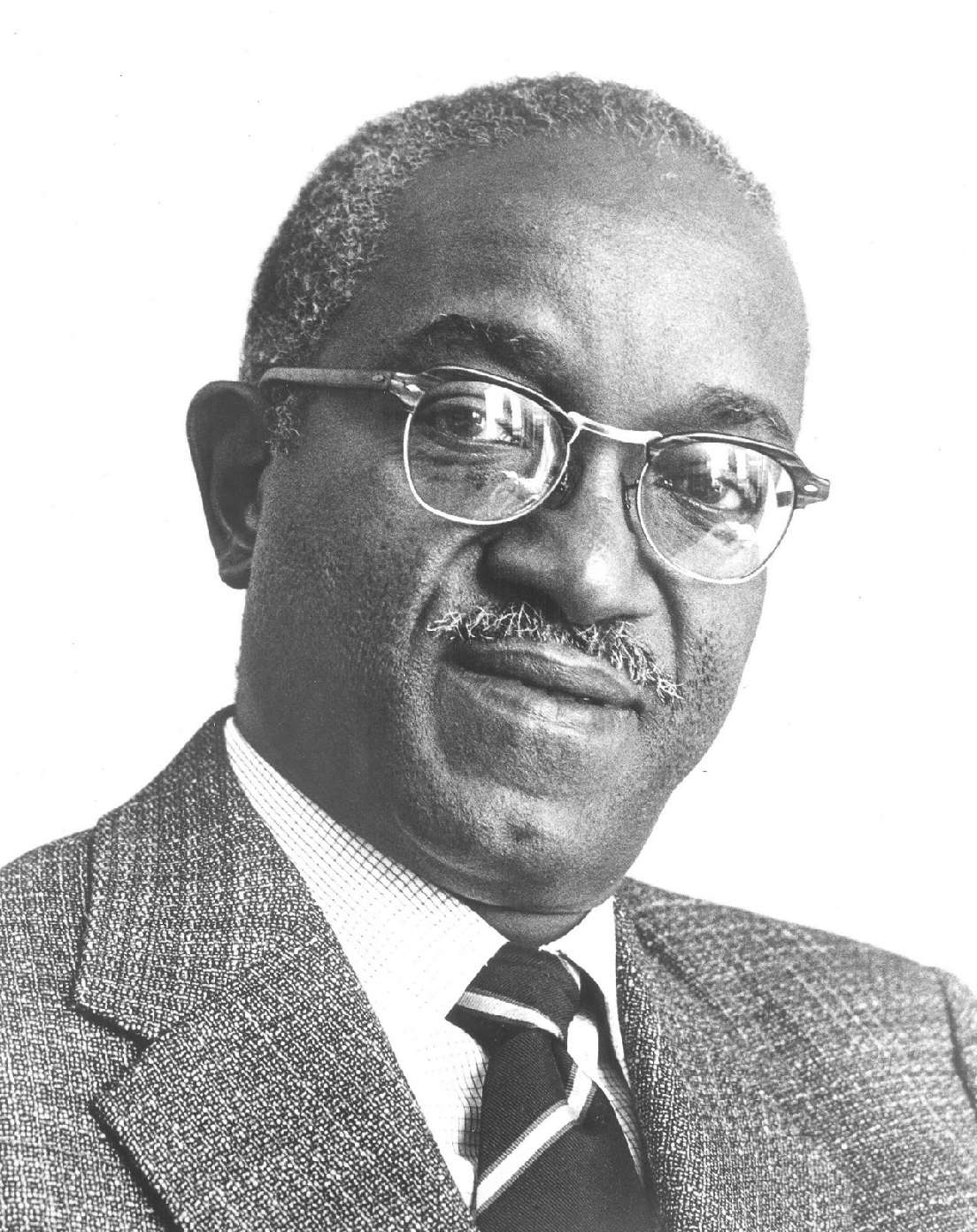

In June 1997 when President Bill Clinton assembled a seven-member panel to advise him about racial strife in the United States, he chose John Hope Franklin as its chair. This was not the first time that the then 82-year-old historian had made history. As a college student, he protested to President Franklin Roosevelt after a local black man was lynched. As a young scholar, he provided historical research for Thurgood Marshall’s brief in Brown v. Board of Education. For Franklin, the task of correcting American history in the light of black experience had always been a crucial part of the fight for racial equality.

Franklin was born in the all-black Oklahoma frontier town of Rentiesville. He moved with his family to Tulsa in 1926. His father, Buck, was a lawyer who resisted segregation in the courtroom and spent every night reading and writing. His mother, Mollie, was a schoolteacher who, along with her children, was once expelled from a train because she would not obey segregated seating rules.

After graduating from the segregated Tulsa public school system, Franklin received a bachelor’s degree from Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, graduating with honors in 1935. He earned a doctorate in history from Harvard University six years later. He spent the early years of his career teaching at historically black colleges and universities, including Fisk, North Carolina Central, and Howard University.

Franklin made the front page of the New York Times in 1956, during the period of school desegregation in the South, when he was hired as the chairman of the all-white history department at Brooklyn College. Brooklyn College president Harry Gideonse said of the appointment, “Maybe it will help the University of Alabama students see that color is not a bar to scholarship.” Despite this recognition of his scholarly accomplishments, Franklin and his family were refused service by 135 real estate agents in New York. When they finally found a house on their own, no New York bank would loan them the money to buy it. In 1967 Franklin moved to the University of Chicago, where he again chaired the history department.

Although Franklin’s books are wide-ranging in their subjects, their cumulative effect has been to continue the work begun by W. E. B. Du Bois and Carter G. Woodson in demonstrating that the study of the black experience is essential to American history. Of his many books, From Slavery to Freedom: A History of American Negroes is the most famous. Since its publication in 1947, From Slavery to Freedom has gone through seven editions (the most recent is subtitled A History of African Americans) and has introduced hundreds of thousands of students to black history. Franklin’s other books include The Free Negro in North Carolina, 1790-1860 (1943), The Militant South (1956), Racial Equality in America (1976), George Washington Williams (1985), and The Color Line: Legacy for the 21st Century (1993).

The recipient of more than 100 honorary degrees, Franklin became James B. Duke Professor of History Emeritus at Duke University in 1985. Among the many organizations that he headed are the American Historical Association, the American Studies Association, and the United Chapters of Phi Beta Kappa. He was also inducted into the Oklahoma Hall of Fame in 1978, served as a delegate to the 21st General Conference of the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in 1980, and received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1995.

Contributed By: Lawrie Balfour