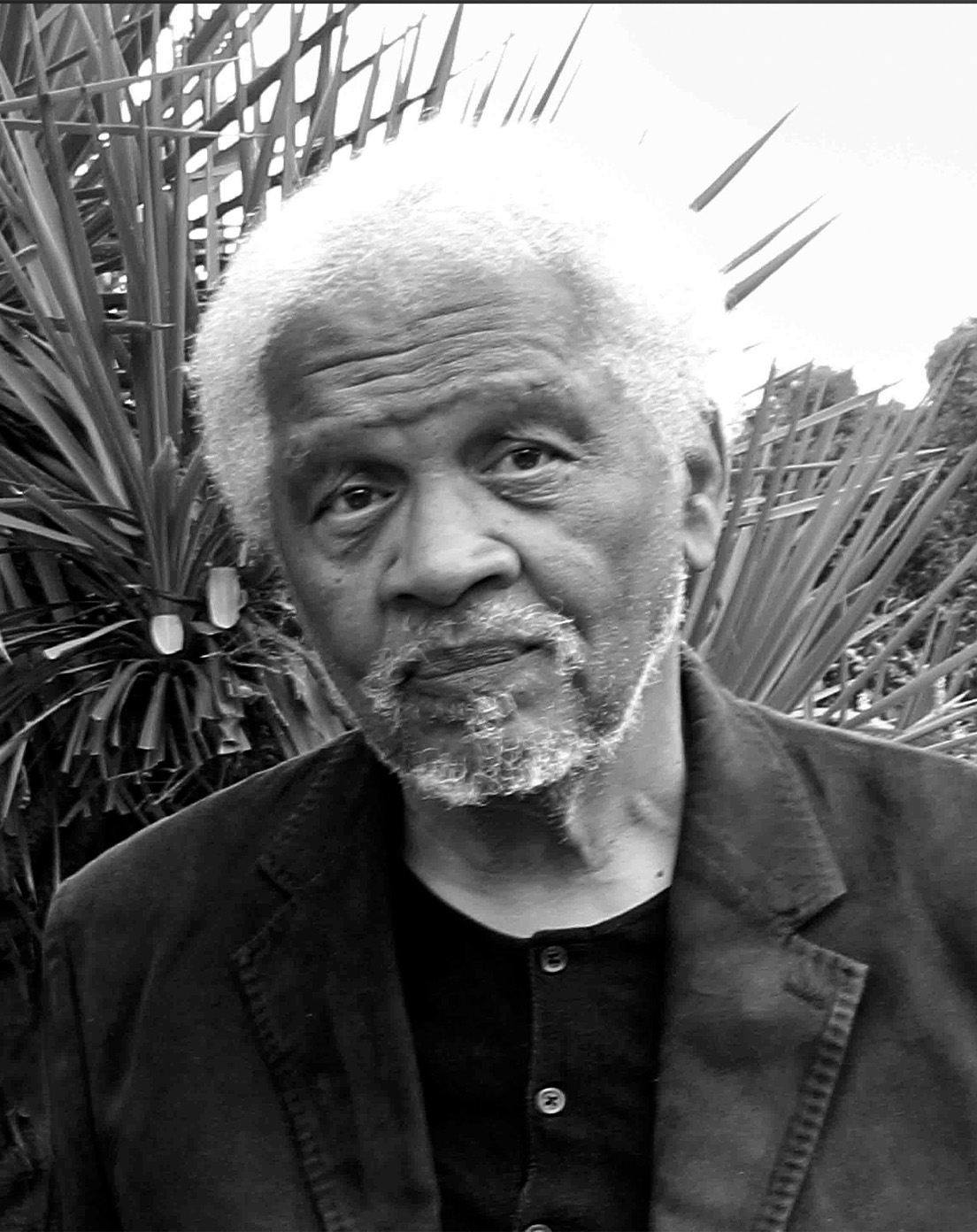

In the introduction to “Of Fear and Strangers: A History of Xenophobia,” George Makari describes a hinge moment in his intellectual life. During his senior year at Brown University, he sat in the office of his mentor, the formidable poet Michael S. Harper:

The poet “stared at me with his wide dead-eye and, clutching a swatch of my empty, late twentieth-century American poems, declared like some sphinx, ‘Makari, where is your history?’ I whispered that I really didn’t know what he meant, but of course I did.”

Embedded in Makari was this shard: In 1974, on the lip of the Lebanese Civil War, George’s parents took him with his two sisters back to their much-loved homeland, where they dodged some heavily armed guerillas blocking the road at night. George was 13. No one in their taxi was harmed, and the family returned to New Jersey some weeks later. But other Makaris became trapped.

“‘Beirut’ was now a warning: this is what happens when neighbors transform into strangers, strangers turn into enemies and society dissolves into a bath of fear and hatred,” Makari writes. “This metamorphosis haunted me, the way good-enough folks could turn into stone-cold killers.”

In 2016, amid the sting of Brexit and the election of Donald Trump, a word kept coming to the psychiatrist’s mind: xenophobia. Long interested in how “we mis-know one another,” Makari “decided to look into it.”

So, the seed of a third book germinated for the director of the DeWitt Wallace Institute of Psychiatry at Weill-Cornell Medical College in New York City. For more than two decades, Makari, as a professor of psychiatry, has led its efforts to integrate humanistic scholarship into mind-brain medicine and science.

His earlier works, “Revolution in Mind: The Creation of Psychoanalysis” (2008) and “Soul Machine: The Invention of the Modern Mind” (2015), have been translated into 9 languages. Their findings have been the focus of eight symposia.

As a third grader in Plainfield, N.J., “Charlotte’s Web” made George Makari a reader. “At home, my father conveyed a love of language when he recited snippets of Arabic poetry, while I devoured everything I could find by Mark Twain, even his lesser efforts such as ‘Tom Sawyer, Detective,’” Makari told Times Higher Education. “For the son of Lebanese immigrants, Twain became my guide to the mythic geographies of America.”

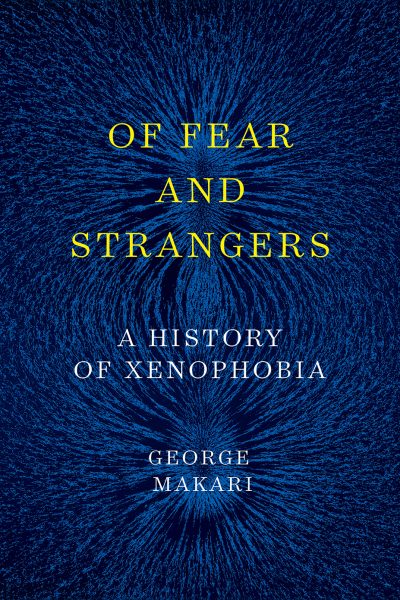

The newest book took Makari five years to write. It is a riveting investigation into the history of an idea, xenophobia, which, unlike racism, antisemitism or homophobia, puts the emphasis on the perpetrator — not the victim — of these irrational fears, bigoted hatreds, and indefensible acts.

“We see countless books that consider instances of racism,” Anisfield-Wolf Juror Steven Pinker notes. “Very few seek to understand it as a phenomenon to be studied and analyzed. ‘Of Fear and Strangers’ does that, free of cliché and jargon. Instead, it is replete with liveliness, wit and original turns of phrase.”

Coined by late 19th-century doctors and political commentators in Europe, xenophobia may be an ancient impulse, but it emerged as a discrete idea alongside Western nationalism, mass migration and genocides. French newspapers made the first general use of it in 1900 to describe Chinese peasants in the Boxer Rebellion shouting “destroy the foreigners” at European missionaries and colonizers.

Makari told the Commonwealth Club that he was shocked to discover that what he assumed was a high-minded, principled term “went viral in France in a very specific racist way.”

Gradually, in the wake of calamities that culminated in the Holocaust, the word came into its current connotations. Makari describes xenophobia as a three-headed monster comprised of problems of identity, irrational emotions and group psychology.

“Words and ideas do things; they change the way we think and act,” he writes. “Xenophobia is one such word.”

The term has re-emerged with such zeal that Dictionary.com made it 2016’s word of the year. Weaving history, philosophy and psychology, Makari looks at xenophobia in light of conditioned response, stereotype, projection and institutional bias. Along the way, he samples the thinking of Sigmund Freud, Simone de Beauvoir, Walter Lippmann and Frantz Fanon; he weighs the fiction of Joseph Conrad and Richard Wright.

“History is a trip through the spirit world,” Makari writes. “It is an attempt to wake the graveyard and give our ancestors voice and form, so we can confront them and free ourselves from their spells.”

The author lives in Manhattan with his wife, the painter and curator Arabella Ogilvie-Makari, to whom he dedicates this book. They have two grown children, Gabrielle and Jack.