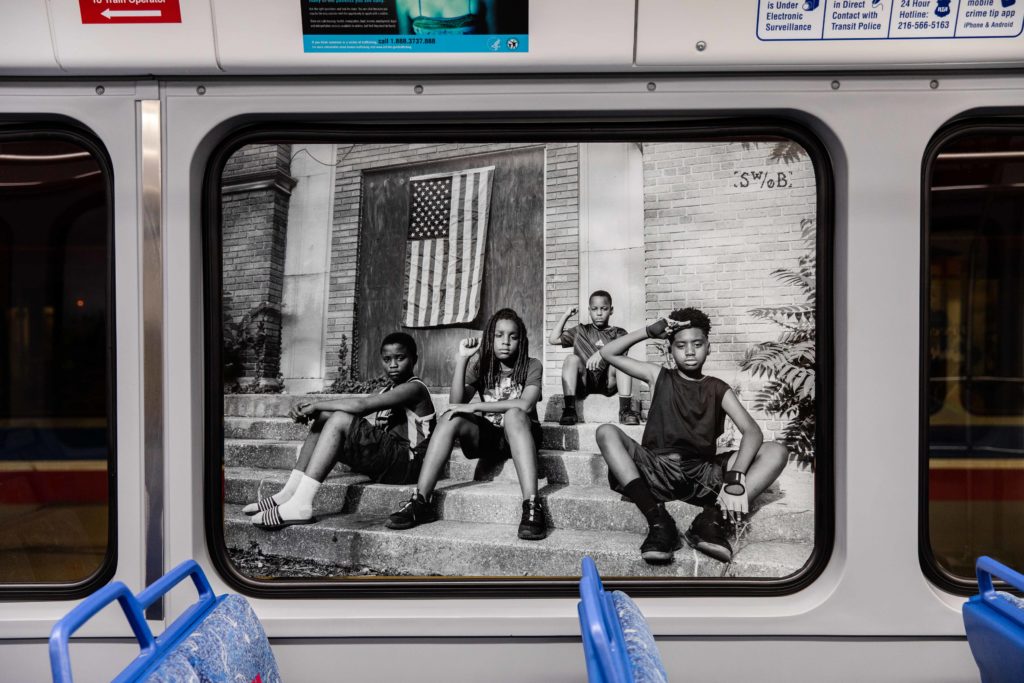

The novelist Tommy Orange grew up in a city – Oakland, California – as the majority of Native American people do. “We know the sound of the freeway better than we do rivers, the howl of distant trains better than wolf howls,” he writes in the prologue to “There There.” It is an incandescent first novel in the voices of 12 Native American characters who converge on a fictional powwow at the Oakland Coliseum.

“Yes, Tommy Orange’s New Novel Really Is That Good” reads last year’s headline in The New York Times. Jurors for the PEN/Hemingway, The Center for Fiction and the National Book Critics Circle all agreed, crowning “There There” with prizes. “This book is a fierce beauty,” notes Rita Dove, a jurist for the Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards.

“There’s been a lot of reservation literature written,” Orange has said. “I wanted to have my characters struggle in the way that I struggled, and the way that I see other Native people struggle, with identity and authenticity.”

The author, an enrolled member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho nations, is the son of parents who met in New Mexico. His mother is white and his father grew up on an Oklahoma reservation. Orange describes his adolescent self as a middling student, someone who occasionally heard slurs from his mostly white high school classmates — they mistook him for Chinese or Mexican. He told The New York Times that often he didn’t feel Indian enough or white enough.

But teenaged Orange threw himself into roller hockey and discovered a love of music, playing first guitar then piano. He graduated in 2004 with a degree in sound engineering, thinking he might do movie work, but jobs were scarce. So, he took a position at a used book store outside of Oakland and began to read. Franz Kafka and Jorge Luis Borges arrested his attention, so did Clarice Lispector, and Lousie Erdrich. “A Confederacy of Dunces” by John Kennedy Toole and “The Bell Jar” by Sylvia Plath became touchstones.

“I fell in love with reading while working at that bookstore, and I felt like I was playing catchup for the next ten years,” Orange told The New Yorker. “At some point in there I started writing, too, and felt even further behind. I became pretty obsessed with reading and writing. I loved what literature could do, how beautiful and transformative and devastating it could be in big and small ways.”

Orange waited tables in New Mexico and worked in a Native Health Center in Oakland. The idea for “There There” came to him in a single moment in 2010, as he was driving to a piano concert. It was the same year he learned he would become a father to his son.

“There’s a dehumanization that’s happened with Native people because of all these misperceptions about what we are,” he told National Public Radio. “And it’s convenient to think of us as gone, or drunks or dumb. It’s convenient to not have to think about a brutal history and a people surviving and still being alive and well today, thriving in various different forms of life, good and bad. I wanted to represent a range of human experiences as a way to humanize Native people.”

Orange has said all the characters in “There There” contain aspects of him. Orvil Red Feather is a 12-year-old boy trying to figure out aspects of his heritage by searching YouTube and by watching videos and television:

“There on the screen, in full regalia, the dancer moved like gravity meant something different for him. It was like break dancing in a way, Orvil thought, but both new – even cool – and ancient-seeming. There was so much he’d missed, hadn’t been given. Hadn’t been told. In that moment, in front of the TV, he knew. He was part of something. Something you could dance to.”

Anisfield-Wolf Juror Joyce Carol Oates found this book “one of the most deeply moving and illuminating works of fiction in recent memory… both a lamentation for a marginalized and fragmentized Indian/Native American/American Indian culture and a celebration of its people in all their idiosyncratic, indefinable, unclassifiable and brilliantly elusive individuality. Here is a novel that moves forward so rapidly, the reader must keep a very quick and attentive pace to keep up.”

In 2016, Orange graduated with an MFA in creative writing from the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico. In recent years, it has become an incubator of indigenous talents, designed and staffed mostly by Native American people. Orange teaches in its graduate program and says his favorite place to write is in a hotel room.

He lives with his wife and son in Angels Camp, California.